Heritage Tourism and the Experience Economy

In his book on Historic Preservation, the author Norman Taylor cites that 80% of vacation travelers in the United States incorporate some aspect of heritage tourism in their trip, meaning they are visiting a place to see local sites, activities, or culture or food that relates to heritage interpretation. This industry has been calculated to contribute $200 billion dollars to the US economy, and therefore is a very important part of the tourism industry in the US and needs to be discussed and analyzed so that it can continue to grow in the best way possible for all constituents.

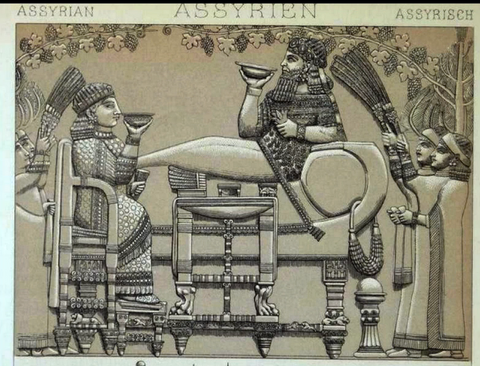

Many parts of heritage tourism are wonderful and contribute positively to society, our understanding of our history and ourselves, and local economies. For instance, Freeman Tilden, a pioneer in the 1940s in identifying heritage interpretation, cited several aspects of this concept which are still used to this day in teaching the goal of heritage tourism. He identified the difference between information and interpretation, noting that information needs to be interpreted in order to create the desired experience for the visitor. Simply providing information does not create the intended experience, which is for the visitors to walk away from the site feeling inspired and provoked, and ultimately, perhaps learning something more about themselves as well as the site or building. Tilden used the words “provocation” and “art” when referring to heritage interpretation, stating that interpretation is an art, and “any art is teachable”. The information should be displayed in a way that relates personally to the visitor, and that “provokes” an emotional response, even a “revelation”. (Taylor, Historic Preservation).

Experience Economy refers to the creating of a “scene” around a historic district or building. For instance, Starbucks created an experience economy on a smaller level around its logo and experience of being in its stores. In the Historic Preservation field, Nantucket can be seen as an experience economy. People come to experience the historic district, and the context and buildings surrounding the whaling industry of the late 18th and early 19th century. Without the historic streets preserved, and the feeling of walking back in time, the impact of the experience would not be as strong. This aspect of heritage tourism provides economic benefits to the town: for instance, people stay at local inns, shop in stores, and eat at local restaurants. The same is true of visiting a historic theater, as tourists tend to do more in the area as they experience local culture via food in restaurants, shopping or bars. This contributes positively to the town’s economy.

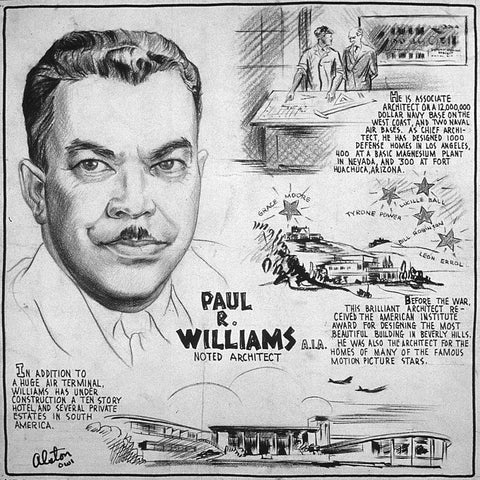

Thus, there are three main benefits to heritage tourism. The first is the ability to share historic sites and experiences as an educational tool which may provoke or inspire ideas and concepts that the visitor had not before experienced. By opening doors to new ways of seeing and interpreting history, we can both learn from and better understand our past. The second is the ability to bridge relationships between different cultures and those whose heritage is being discussed. By preserving sites in the Historic Preservation community, we open the door to conversations about those sites and have the ability to learn from and appreciate the needs of all stakeholders. The third is the economic impact on a community by opening its doors to heritage tourism: whether its special and wonderful sites or its intangible heritage such as song, dance, or activities local to the community. A by-product of the benefits to heritage tourism is the increased focus on the need for Historic Preservation as a field: to study, appreciate, and learn best how to care for these historic resources, properties and their context.

However, there are also some drawbacks to heritage tourism, including what is called “Thanatourism”, literally translated “Death Tourism”, from the Greek work “Thanatos”. Also known as as “Dark Tourism”, this sector of heritage tourism refers to tourism to sites relating to death or horrible events, such as The Holocaust, Slavery, or the Japanese internment camps in California. Our nation has a difficult and often controversial past, and thus some sites and historic parts of heritage tourism can be controversial, provoking strong emotional and upsetting responses in visitors. Often these sites are called “contested” in the historic preservation field, and lately more attention has been paid in how to handle the visitor experience to sites that deal with slavery, war, or inhumane treatment of people. Taylor points out that in every war there are some who were victors, and some who were slaughtered, provoking different responses based on one’s point of view. These sites need to be carefully explained and interpreted, in order to be sensitive to different viewpoints. Native American war sites are an example, and some have been renamed to be more culturally thoughtful. Another example of a thoughtful yet provocatively re-done site of Thanatourism is Manzimar in California, the Japanese internment camp in 1942-1945. The site has been carefully designed with an eye to all stakeholders, by providing an experience that addresses the emotions and atrocities of the site. Yet another is the preservation of slave households, where visitors in the South can stay and firsthand experience what it would have been like to be there.

In conclusion, Heritage Tourism is an important aspect of the general tourism industry in the United States, and of the field of Historic Preservation. Without careful and thoughtful preservation, whether restoration to a specific period in time, rehabilitation of old and important sites, adaptive use of old buildings, and the work of the National Landmarks Committees and Preservation boards, including at the local and community level, there would be no sites or buildings preserved for people to visit. I believe that having the experience of seeing a local culture in its place of development, learning about an important historical style in its context, and seeing a building of an important person or event in history firsthand is an invaluable way for people to experience history, and far superior to learning in a textbook. There is even a place for “contested” or difficult history, if the time is taken to involve all constituents and listen to all you are affected by that site. If we do not keep our history to learn from it, we have wasted a valuable resource to learn to both do better that which worked well for our country and avoid the horrific failures in our country’s past.